Scientific Facts

| Common Name | White-winged Crossbill / Two-barred crossbill |

| Scientific Name | Loxia leucoptera |

| Size | 15 cm |

| Life Span | 4 years |

| Habitat | Coniferous forests |

| Country of Origin | North America |

Physical Description

Adult Male

Beak rather lengthy, corpulent at the root, where it is higher than comprehensive, remarkably packed near the end, the bones towards their foot diverted to different sides, to intersect each other. Upper mandible with the rear line curved and diverted, the sides somewhat arched, the corners honed, and towards the edge associated, as in Rhynchops nigra, the peak extremely compact, decurved, and stretching distant away that of the opposite. Lower jawbone with its corner very small and large, the rear frame sprouting and bent, the edges acute, crooked, and resembled at the peak, which is notably clever. Snouts tiny, natural, curled, concealed by short fuzzy plumage.

Head huge, broadly elliptical; neck short; eyes small; body dense. Feet somewhat small, robust; anklebone compact, compressed, with seven anterior scutella, and two hind strata joining to create a narrow edge; toes of medium size, the outer fused at the base, the initial tough, the side toes almost equal, the third much enlarged; the papillae and pads of the feet extremely large. Hooks long, bent, very slim, much shortened, and narrowing to a fine tip.

Plumage blended. Wings of ordinary length, pointed, the outer three primaries longest (in one specimen the first longest, in three the second); secondaries slightly emarginate. The tail of moderate length, deeply emarginate, the feathers curved outwards at the point.

Beak shady, spattered with greyish-blue, particularly on the corners. Optics hazel. Claw deep reddish-brown. The overall tone of the feather is bright carmine, tending to red; the plumage on the facade and core of the rear dusky, excepting the points; the shoulders, plumes, upper tail-coverts, and tailpiece black; two wide strips of white on the appendage, the anterior created by the initial line of tiny coverts and various of those uniting, the other by the subsequent coverts, of which the basal half only is black; the innermost secondaries are tilted with white, as are the tail-coverts, and the feathers and tail-feathers are very somewhat bordered with whitish. Hairy plumage at the root of the beak yellowish-white; surfaces brownish, and barred with fuzzy, axillar plumages whitish; more profound tail-coverts brownish-black, widely fringed with reddish-white.

Female

The female has the higher portions ebony, the plumage bordered with greyish-yellow, the bottom wax-yellow; the lower sections are yellowish-grey, barred with tawny, the facade of the thorax wax-yellow; the plumes and tailpiece are similar with the male, though lighter, and with the white stripes on the former of smaller size. Beak and toes darker than those of the male.

Young

The juvenile matches the female, though the lower sections are deep yellowish-grey, blotched, and barred with dull brown.

Following the initial shed, the male yet mirrors the female; however, it is more yellow. In the subsequent shed, it obtains the red shade, which grows brighter and clearer the older the bird.

In this breed, there are three lengthwise crests on the cover of the muzzle, and the tongue is curved in an identical way as in Buntings. The palate is of the very overall figure as that of the Pine Grosbeak, 3 1/2 twelfths long, compacted and slim at the foot, with the basihyoid ossein of a comparable structure, cupped above, expanded and curved at the tip, to match a spoon or scoop. The esophagus is 5 centimeters and 20 cms long when enlarged produces a crop of huge size, which rests mainly on the right facade of the collar, though also crosses behind to rise on the left side. This pattern transpires identically in the Common Crossbill and appears to be eccentric to this genus.

The most comprehensive extent of the crop is 10 twelfths. On entering the abdomen, the esophagus shrinks to 5 cms. The proventriculus is tuber-form, with a width of 7 cms. The belly is a powerful innard of somewhat modest size, slightly twisted in the identical method as that of the Pine Grosbeak; its muscles well-defined; the cuticular covering very sturdy but delicate, longitudinally rugous, and of a light red color.

Geographical Range

The White-winged Crossbill has a profoundly unsteady breeding population in Canada and several of the lands in the northern portions of the United States, plus dispersed regions of the Rocky Mountains. Some of the highest documented masses have remained in Labrador, northeastern British Columbia, southwestern Alberta, and northern Manitoba. A subspecies (L. l. bifasciata) transpires in the entire Palearctic zone from northern Scandinavia to Siberia.

Habitat

All season, White-winged Crossbills populate cone-bearing woodlands, feasting principally on tamarack seeds and spruce. Like Red Crossbills, they happen throughout the woods of Engelmann spruce, and balsam fir and white, red, black. Though, they are rare or nonexistent in most hemlock, pine, and Douglas-fir woodlands owned by Red Crossbills. During times of low food stocks, numerous White-winged Crossbills roam distant away from the area. At such events, they frequent environments that range from weedy meadows to flowery farmings to pine woods. Their inclination is for spruce varieties, and during incursion winters, they are drawn to tiny stations of spruce, as often located in older graveyards, arboretums, or school faculties.

Common Behavior

White-winged Crossbills normally start nesting early in the year, frequently in late winter. They have been documented nesting in every month, whenever food is abundant. Exposing males roost high in spruces, sometimes in tiny groups, and start caroling. When females advance, males often track them in flight, and coupled birds start to link by nipping each other’s beaks. Males additionally foster females in dating, disgorging a paste of spruce grains toward their beaks.

White-winged Crossbills look to hold a monogamous coupling arrangement, but no research has decisively verified this. Structural similarities to Red Crossbills propose White-winged males may be modified to endeavor extra-partner matings. Males do lookout females intimately after coupling, tracking away other males, and they protect the retreat wood as well though do not build a feeding area, presumably since food is so abundant throughout the nesting period. Males solely heed for the juvenile after maturing, and it is conceivable that females then partner to produce a second offspring (a practice identified as serial polyandry), as goldfinches and redpolls likewise make.

White-winged Crossbills crowd all season, but in moments of food deficiency, males lead to control females at food origins, and more grown birds control more youthful ones. Their menace show includes tilting near an invader and opening the beak. Searching in flocks enables crossbills to savor the advantages of possessing more eyes viewing for predators. They may likewise talk about cone products, swiftly recognizing and advancing toward woods that produce superior grains.

Diet and Feeding Habits

White-winged Crossbills particularize in feeding grains from the cones of tamarack and spruce, the basis of their nutrition for most of the cycle. When tamarack and spruce seeds are limited, they pick fir grains. During summer, they consume insects, oddly cone worm, and spruce budworms, along with spiders, bugs, and ants. Less commonly, they have flowers of ephemeral trees, and bulbs of pine (eastern white pine, red pine), ragweed, goldenrod, sunflower, sweetgum, cottonwood, birch, alder, eastern redcedar, eastern hemlock, and various grasses and sedges. They consider such substitute foods mostly throughout outbreak years, in which immense numbers abandon the boreal woods since cone yields are low.

To pluck seeds from conifer cones, White-winged Crossbills normally clasp the cone with one claw and snap the cone where the coverings adhere, revealing a break within the flakes, which can be enlarged with more power of the beak and by turning the head. The seed can then be removed utilizing the longer upper mandible and tongue. They commonly hunt in trees, though usually serve on spruce cones that have dropped to the area, which are more malleable than appended cones. The birds then peel the seed (discard the seed cover) and consume the seed entirely. To aid crush their food, White-winged Crossbills devour tiny amounts of shingles, frequently from tracks or verges.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

2-4, infrequently 5. Whitish to light blue-green, including brown and lavender blemishes focused at the larger tip. Incubation is by female, presumably 12-14 days. Male nurses female throughout incubation. Juvenile: Female wastes much extent sitting juvenile at first, while the male delivers meals; succeeding, both origins serve chicks. The age at which juvenile abandon the cradle is not distinguished. Male may heed for offsprings while female starts another dwelling endeavor.

How to Breed

The breeding period of White-winged Crossbills is more strictly bound to food accessibility than it is to season. They can breed at any moment of the cycle, frequently in mid-winter, if there is an overflowing source of grains. They may be equipped to breed as juvenile as five months old and can produce multiple clasps in a year. This occurs in high generative germination. They are monogamous, and partners develop within flights. The female constructs the den, which is commonly on a straight branch uppermost in a spruce tree. The cradle is an open vessel of branches, grasses, weeds, and cork layers, filled with roots, lichen, moss, and fiber. The female nurses 2 to 4 eggs for nearly 12 to 14 days. The male carries food to the fostering female and the juvenile for the initial several days after they brood.

Following roughly five days of endless brooding, the female couples the male in delivering food to the juvenile. The juvenile abandons the cradle subsequent about 18 to 22 days. Once the young mature, the male may remain to heed for them while the female starts a secondary clutch. The juvenile birds’ jawbones start to intersect about two weeks after they matured, and they discover to remove seeds shortly after that.

Pet Care

The range is the answer to a comprehensive crossbill environment.

Crossbills require a scope to circumnavigate horizontally more than they demand perpendicular extent. This is necessary since it is their sole method of training. A couple of crossbills must have a least of 75 centimeters lengthwise.

How to care for finches

Enclosures must be placed in calm spaces with low meter movement to lessen pressure on the birds. Enclosure coverings are generally kraft paper or newspaper. Assume to wash the enclosure hebdomadally and thoroughly sanitize the enclosure once per month.

Crossbills are not huge enthusiasts of playthings, though they do fancy swings and perches. Since the birds navigate horizontally, make certain these things do not prevent or hinder the gliding route. Have them away from water and food origins, so dropping excrements do not pollute their nutritional matters.

A log cannot be sanitized once stained by excrements, so non-toxic wood elements or twigs are approved. Refrain cedar, redwood, or pressed-wood chips (fatal to birds); rod roosts (feet obstacles); and sandpaper-covered perches (lethal).

Water and food vessels must be non-toxic plastic or stainless steel to minimize bacteria and disease.

It’s likewise a great plan to hold an extra set; when washing the current vessels, you can substitute them with the additional ones. Water and food bowls can be positioned on opposing edges of the enclosure to enhance training.

Availability

White-winged Crossbill availability is tricky to calculate, as these birds reproduce in the distant north and are roaming, implying they can be locally sufficient in some years but absent the next.

Image Source https://www.coniferousforest.com/white-winged-crossbill.htm

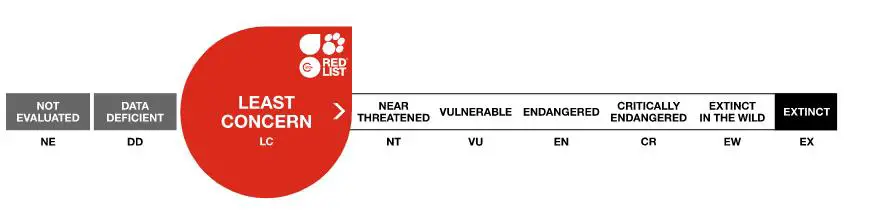

Conservation

There is presently limited conservation interest for the White-winged Crossbill, with a record of 7 out of 20 by Partners in Flight. Among the causes for the number are its constant distribution and its extremely broad Holarctic population across Asia, northern North America, and Europe. Environment Canada takes discretion that “large-scale conservation that lessens the age-class population of spruce forests enough to restrict cone formation could be adverse.” Moreover, Fowells remarked that maximum cone formation does not transpire until woods are beyond 60 years of age.

Numerous researchers have defined the essence of conifer seed accessibility as a constraint on White-winged Crossbill distributions. When grain availability is flat, the species is more ambulant, and extinction, particularly among younger birds, is more comprehensive. Benkman recorded that wide-scale preservation in areas of the North American continent may be necessary because cone production throughout any year can be profound in one or more areas of the mainland. Therefore, a system of adequate areas across the mainland may be crucial for the long-term continuance of this species.

Climate change is likewise a dormant menace to this species due to its northerly population. The National Audubon Society and Langham et al., in its review of environment responsiveness of North American bird species, classified the White-winged Crossbill as “climate threatened.” The reason for this classification was the implied decline of 85% of its prevailing summer scale by 2080. Moreover, they proposed that recently accessible territory to the north would require to be established by tiny-coned conifers such as fir, spruce, or tamarack. Generally, speculation on the existence of a current adequate environment offers a dangerous eternity for this species if weather modification remains.

Facts

- Mature White-winged Crossbills shed their plumages once a year, commonly in the fall. The red plumes of the male possess an uncolored beard that conceals the red and gives the bird seem pink at first in the autumn. As these beards fizzle out, the rich red displays through, causing the summer and spring male brightly colored.

- Specific White-winged Crossbills can consume up to 3,000 conifer grains every day.

- White-winged Crossbills are devious breeders; they can begin dwelling at any period in the year when food is adequate for the female to produce eggs and support juvenile. The species has been documented breeding in all 12 months.

- White-winged Crossbills with lower jaws joining to the right are nearly three times more prevalent than those with lower jawbones meeting to the left.

- In Europe, the White-winged Crossbill is recognized as the “Two-barred” Crossbill. This Old World kind is greater than New World birds, with more extensive beaks, limited black in the feathers, various cries. The two forms are presently viewed as identical species, though they may be separate species.

FAQs

What do crossbills employ their feet for?

Crossbills are particularist feeders on conifer cones, and the unique beak pattern is compliance that allows them to pluck grains from cones. These birds are generally located in higher northern hemisphere ranges, where their food sources develop.

What do white-winged crossbills eat?

White-winged Crossbills specialize in consuming grains from the cones of spruce and tamarack, the fundamentals of their nutrition for most of the year.

How long does white-winged crossbill live?

In confinement, one crossbill was identified to have existed for 4 years. In the wilderness, they don’t survive as long, merely 4-5 years

What does a crossbill look like?

Mature males are brick red overall, with duller tail and wings. Females are chiefly yellowish below, olive-brown or brownish above. Immatures are brownish above, light with brownish smearing below.

What is a crossbill habitat?

Crossbills prefer older coniferous forests, particularly larch, hemlock, Douglas-fir, pine, or spruce, with recent cone crops.

How does a crossbill use its beak?

A crossbill uses this particular beak for a specific objective: forcing pinecone flakes apart. Crossbills can likewise utilize their superior beaks to consume insects, fruit, and other grains.